Reimagining the Relationship Between Architecture and Identity

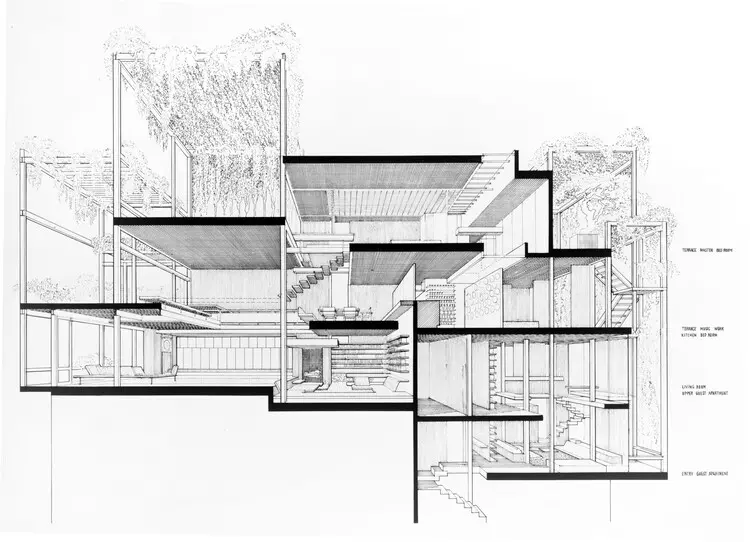

Paul Rudolph, Rudolph Apartment at 23 Beekman Place, New York (1977-1997). Perspective Section, 1997.

Paul Rudolph, Rudolph Apartment at 23 Beekman Place, New York (1977-1997). Perspective Section, 1997.

A growing number of theorists and practitioners have been discussing the impact of gender and race on the profession and theory of architecture. However, the relationship between the built environment, sexual orientation, and gender identity remains understudied. This article aims to shed light on this neglected area of design theory and explore the potential of queer space theory in the teaching, study, and practice of spatial design.

Separate Spaces: Questioning Private and Public

Understanding the role of gender and sexuality in relation to architecture and space necessitates a deconstruction of the binaries that dominate architectural discourse. The opposition of public and private is grounded in a prior spatial dualism, that of inside and outside. Architecture's bounding surfaces reinforce cultural gender differences by regulating the flow of people and the distribution of objects in space. This understanding builds on the concept of separate spheres, which posits that men occupy the public sphere while women inhabit the private sphere. However, this binary understanding of space fails to capture the complexity and fluidity of human experience.

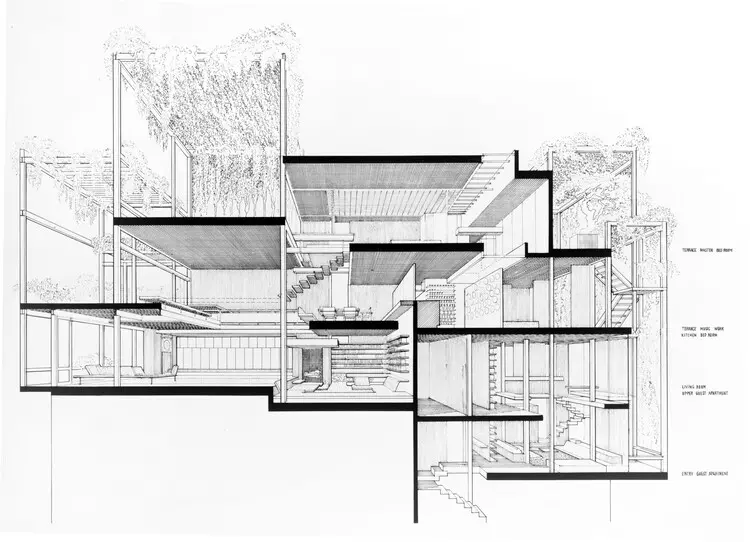

Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative, Matrix Feminist. Architectural Co-operative (s.d.). Brochure published in London.

Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative, Matrix Feminist. Architectural Co-operative (s.d.). Brochure published in London.

The association of domesticity with femininity has often relegated women architects to the design of interior, domestic spaces. Yet, this limitation has also provided an opportunity for women designers to engage in important debates on the production of healthy bodies and the constitution of new subjects. The feminist questioning of traditional approaches to architecture has led to the emergence of practices focused on design accessibility for all, challenging existing social, spatial, and economic structures that limit access to architecture and public spaces. However, women and other minorities still face barriers in accessing the architectural profession, highlighting the need for further progress.

"Queer": Identity, Movement, or Theory?

The term "queer" has a contested history, originally used pejoratively but later reclaimed by activists and scholars. It has come to represent an activist/political movement and a theoretical approach that challenges traditional categories of gender and sexuality. Queer theory goes beyond the realm of sexual and gender identities, critiquing conventional identity politics and emphasizing the performative nature of gender and sexuality. This understanding of queer has inspired academic discussions of queer space, highlighting its potential for expanding the teaching, study, and practice of spatial design.

Queer Space Theories: Deconstructing Spatial Binaries

Queer space theories offer multiple understandings of queer space and its relation to architecture. One approach views queer space as gay or lesbian territory, demarcated from heteronormative space and representing the physical manifestation of a gay community. Another approach focuses on the sexualized aspects of queer space, emphasizing sexual acts and tension as defining features. A more expansive understanding of queer space sees it as challenging and imminent, in a constant process of construction in opposition to heteronormativity. This understanding emphasizes the performative nature of queer space and its dependence on context and relationality.

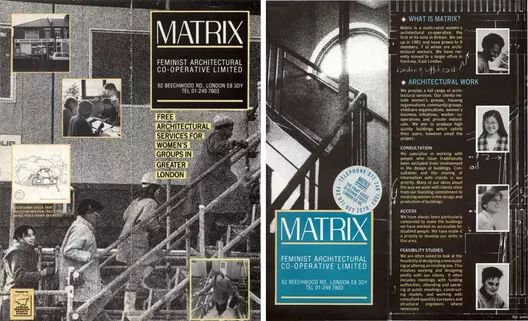

Elmgreen & Dragset, Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under Nazism (2008).

Elmgreen & Dragset, Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under Nazism (2008).

While these theories contribute to the understanding of queer space, they also raise important questions about the physical characteristics of queer space and the boundaries of its definition. Can any space become queer? Are spaces commonly associated with LGBT people queer? The answers lie in the recognition of the performative nature of space, its constant construction through human interactions, and its intersection with various elements of identity, such as gender, race, class, and age.

Towards Other Spaces

The development of queer theory and activism has brought attention to the idea of heteronormativity, which enshrines heterosexuality as normal and positions non-heterosexual individuals as Other. However, it is essential to avoid the conflation of all heterosexual identities into a single normative category and to recognize the diverse identities within the queer community. The focus on white gay men in discussions of queer space is limiting and fails to address the complexity of identity. We must expand our understanding of the built environment and its relationship to identity, allowing everyone to express the diversity, complexity, and fluidity of their identities.

Harwell Hamilton Harris, Weston Havens House, Berkeley (1940). Section published on the cover of California Arts & Architecture.

Harwell Hamilton Harris, Weston Havens House, Berkeley (1940). Section published on the cover of California Arts & Architecture.

The future of architecture lies in challenging normative structures and embracing a more inclusive approach to design. This requires considering sexual orientation, gender, age, ethnicity, culture, and class in the creation of spaces that cater to a diverse range of individuals. It also demands a reevaluation of traditional concepts of private and public, physical and digital, and the development of new models of community that disrupt contemporary ways of living. By embracing a queer perspective on spatial thinking, we can create environments that meet the needs of everyone and challenge oppressive normativity.

This article highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between architecture and identity, emphasizing the potential of queer space theory in reshaping the teaching, study, and practice of spatial design. It calls for a shift away from binary thinking, a questioning of heteronormative structures, and a more inclusive approach that acknowledges the complexity and fluidity of human experience. By embracing these principles, architecture can become a powerful tool for fostering diversity, equality, and social progress.