Redlining is a discriminatory practice that has had a profound impact on minority communities in the United States. This practice refers to the withholding of services, such as financial assistance and insurance, from neighborhoods deemed "hazardous" or high-risk for investment. These neighborhoods are often home to racial and ethnic minorities, as well as low-income residents.

While redlining is most commonly associated with denial of credit and insurance, it also extends to other services, including healthcare and access to quality food options. For example, the deliberate placement of supermarkets far from minority neighborhoods creates a redlining effect, known as a food desert.

Reverse redlining is another form of discrimination, where lenders or insurers target majority-minority neighborhoods with inflated interest rates. This practice takes advantage of the lack of lending competition in these areas. Reverse redlining can also occur when real estate supply is restricted for nonwhite individuals, leading to higher rates as a pretext.

The term "redlining" was coined in the 1960s by sociologist John McKnight to describe discriminatory banking practices that classified certain neighborhoods as "hazardous" due to their racial demographics. Black inner-city neighborhoods were often the most affected by redlining, with Pulitzer Prize-winning investigations revealing that banks would lend in lower-income white neighborhoods but not in middle-income or upper-income Black neighborhoods.

The history of redlining in the United States reflects the systemic racism that has had far-reaching consequences, including educational and housing inequalities across racial groups. Redlining is a manifestation of spatial and economic inequality, contributing to the ongoing segregation of communities and the perpetuation of the racial wealth gap.

The discriminatory practice of redlining began with the National Association of Real Estate Boards and the theories about race and property values developed by economists like Richard T. Ely. The federal government became involved with the National Housing Act of 1934 and the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The FHA formalized the redlining process, accelerating the decay and isolation of minority neighborhoods through the withholding of mortgage capital.

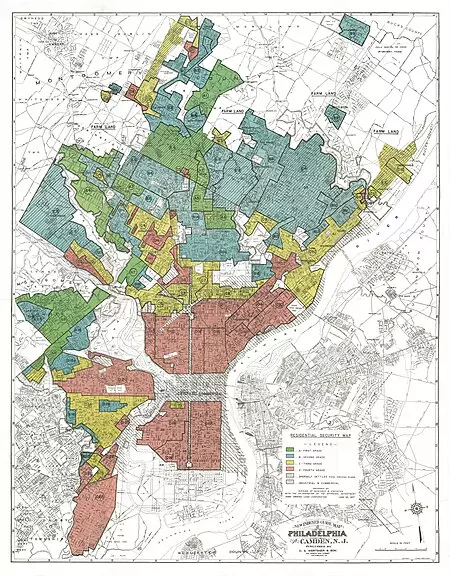

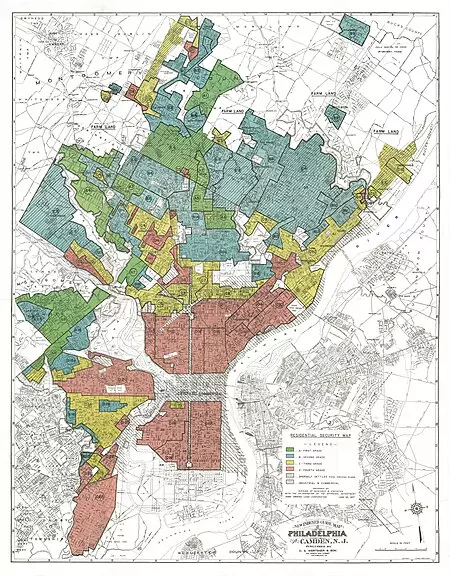

Click here for image source.

Caption: A 1937 HOLC "residential security" map of Philadelphia, classifying various neighborhoods by estimated "riskiness" of mortgage loans.

Caption: A 1937 HOLC "residential security" map of Philadelphia, classifying various neighborhoods by estimated "riskiness" of mortgage loans.

Redlining maps became widespread, and private organizations also created their own maps to meet the requirements of FHA underwriting manuals. Discriminatory lending practices persisted, with African Americans receiving less than 2% of all federally insured home loans between 1945 and 1959.

Redlining practices were not limited to banks and mortgage lenders. Property insurance companies also engaged in redlining, denying coverage or charging higher rates to communities of color. In some cases, redlined neighborhoods experienced higher levels of environmental pollution, as hazardous waste sites were disproportionately located in these areas.

Efforts to combat redlining have included legislation such as the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act. These laws aim to prevent discrimination in housing and credit transactions based on race, color, religion, and other factors. The Community Reinvestment Act, passed in 1977, requires banks to apply the same lending criteria in all communities.

Regulatory lawsuits have also held financial institutions accountable for redlining practices. For example, Associated Bank and Evans Bank settled charges of redlining, leading to financial penalties and requirements to open branches in non-white neighborhoods.

Community organizations have played a vital role in fighting against redlining. ShoreBank, a community development bank in Chicago, provided financial services to African American communities. The fight against redlining also led to the formation of organizations like the National People's Action (NPA), which advocated for disclosure regulations and laws to address lending patterns.

Redlining continues to have lasting effects on communities today. Racial segregation, the racial wealth gap, and environmental racism are all linked to the legacy of redlining. Retail redlining and digital redlining are also forms of discrimination that perpetuate inequities in access to goods, services, and information.

Efforts to reverse the effects of redlining include targeted investments in struggling communities, improved transportation, neighborhood revitalization programs, and equitable distribution of resources. Addressing redlining is crucial for achieving health equity, reducing the racial wealth gap, and promoting social justice for all Americans.

Redlining is a dark chapter in American history, but by understanding its legacy and taking action to reverse its effects, we can work towards a more inclusive and equitable society for future generations.