Do you need strong writing skills to succeed in finance? Not necessarily, but they certainly help. But you definitely need strong reading comprehension skills, or you’ll miss crucial information and make the wrong decisions as a result. Both of these skills intersect in the confidential information memorandum (CIM) that investment banks prepare for clients - the same CIM that you’ll be spending a lot of time reading in private equity, corporate development, and other buy-side roles.

What is a CIM?

The Confidential Information Memorandum is part of the sell-side M&A process at investment banks. It’s also known as the Offering Memorandum (OM) and Information Memorandum (IM), among other names. At the beginning of any sell-side M&A process, you’ll gather information on your client (the company that has hired you to sell it), including its products and services, financials, and market. You turn this information into many documents, including a shorter, 5-10 page “Executive Summary” or “Teaser,” and then a more in-depth, 50+ page “Confidential Information Memorandum.” You start by sending the Teaser to potential buyers; if someone expresses interest, you’ll have the firm sign an NDA, and then you’ll send more detailed information about your client, including the CIM. You can write CIMs for debt deals, as well as for distressed M&A and restructuring deals where your bank is advising the debtor. You might write a short memo for equity deals, but not an entire CIM.

The Order and Contents of a Confidential Information Memorandum

The structure of a CIM varies by firm and group, but it usually contains these sections:

- Overview and Key Investment Highlights

- Products and Services

- Market

- Sales & Marketing

- Management Team

- Financial Results and Projections

- Risk Factors (Sometimes omitted)

- Appendices

Debt-related CIMs will include the proposed terms - interest rates, interest rate floors, maturity, covenants, etc. - and details on how the company plans to use the funding.

What a Confidential Information Memorandum is NOT

First and foremost, a CIM is NOT a legally binding contract. It is a marketing document intended to make a company look as shiny as possible. Bankers apply copious makeup to companies, and they can make even the ugliest duckling look like a perfectly shaped swan. But it’s up to you to go beneath the dress and see what it looks like without the makeup and the plastic surgery. Second, there is also nothing on valuation in the CIM. Investment banks don’t want to “set the price” at this stage of the process - they would rather let potential buyers place bids and see where they come in. Finally, a CIM is NOT a pitch book. Here’s the difference:

Pitch Book: “Hey, if you hire us to sell your company, we could get a great price for you!” CIM: “You’ve hired us. We’re now in the process of selling your company. Here’s how we’re pitching it to potential buyers and getting you a good price.”

Why Do CIMs Matter in Investment Banking?

You will spend a lot of time writing CIMs as an analyst or associate in investment banking. And in buy-side roles, you will spend a lot of time reading CIMs and deciding which opportunities are worth pursuing. People like to obsess over modeling skills and technical wizardry, but in most finance roles you spend FAR more time on administrative tasks such as writing CIMs (or reading and interpreting CIMs). In investment banking, you might start marketing your client without creating a complex model first (Why bother if no one wants to buy the company?). And in buy-side roles, you might look at thousands of potential deals but reject 99% of them early on because they don’t meet your investment criteria, or because the math doesn’t work. You spend a lot of time reviewing documents and comparatively less time on in-depth modeling until the deal advances quite far. So you must be familiar with CIMs if your job involves pitching or evaluating deals.

Show Me the Confidential Information Memorandum Example!

To give you a sense of what a CIM looks like, I’m sharing six (6) samples, along with a CIM template and checklist:

- Consolidated Utility Services - Sell-Side M&A Deal

- American Casino - Sell-Side M&A Deal

- BarWash (Fake company) - Sell-Side M&A Deal

- Alcatel-Lucent - Debt Deal

- Arion Banki hf (Icelandic bank) - Debt Deal

- Pizza Hut - Debt Deal

- Sample Deal - CIM Template

- Information Memorandum Checklist

To find more examples, Google “confidential information memorandum” or “offering memorandum” or “CIM” plus the company name, industry name, or geography you are seeking.

Picking an Example CIM to Analyze

To illustrate how you might write a CIM as a banker and how you might interpret a CIM in buy-side roles, let’s take a look at the one above for Consolidated Utility Services (CUS). This one has the standard sections, though it omits the Risk Factors and Appendices, resulting in a somewhat shorter (!) length of 58 pages. This CIM is ancient, so I feel comfortable sharing it and explaining how I would evaluate the company.

CIM Investment Banking: How Do You Create Them?

This CIM creation process is quite tedious for bankers because it consists of a lot of copying and pasting from other sources. You’ll spend 90% of your “thinking time” on just two sections: the Executive Summary/Investment Highlights in the beginning and the Financial Performance part toward the end. You may do additional research on the industry and the company’s competitors, but you’ll get much of this information from your client; if you’re working at a large bank, you can also ask someone to pull up IDC or Gartner reports. Similarly, you won’t write much original content on the company’s products and services or its management team: you get these details from other sources and then tweak them in your document. The Executive Summary section takes time and energy because you need to think about how to position the company to potential buyers. You attempt to demonstrate the following points:

- The company’s best days lie ahead of it. There are strong growth opportunities, plenty of ways to improve the business, and right now is the best time to acquire the company.

- The company’s sales are growing at a reasonable clip (an average annual growth rate of at least 5-10%), its EBITDA margins are decent (10-20%), and it has relatively low CapEx and Working Capital requirements, resulting in substantial Free Cash Flow generation and EBITDA to FCF conversion.

- The company is a leader in a fast-growing market and has clear advantages over its competitors. There are high switching costs, network effects, or other “moat” factors that make the company’s business defensible.

- It has an experienced management team that can sail the ship through stormy waters and turn things around before an iceberg strikes.

- There are only small risks associated with the company - a diversified customer base, high recurring revenue, long-term contracts, and so on, all demonstrate this point.

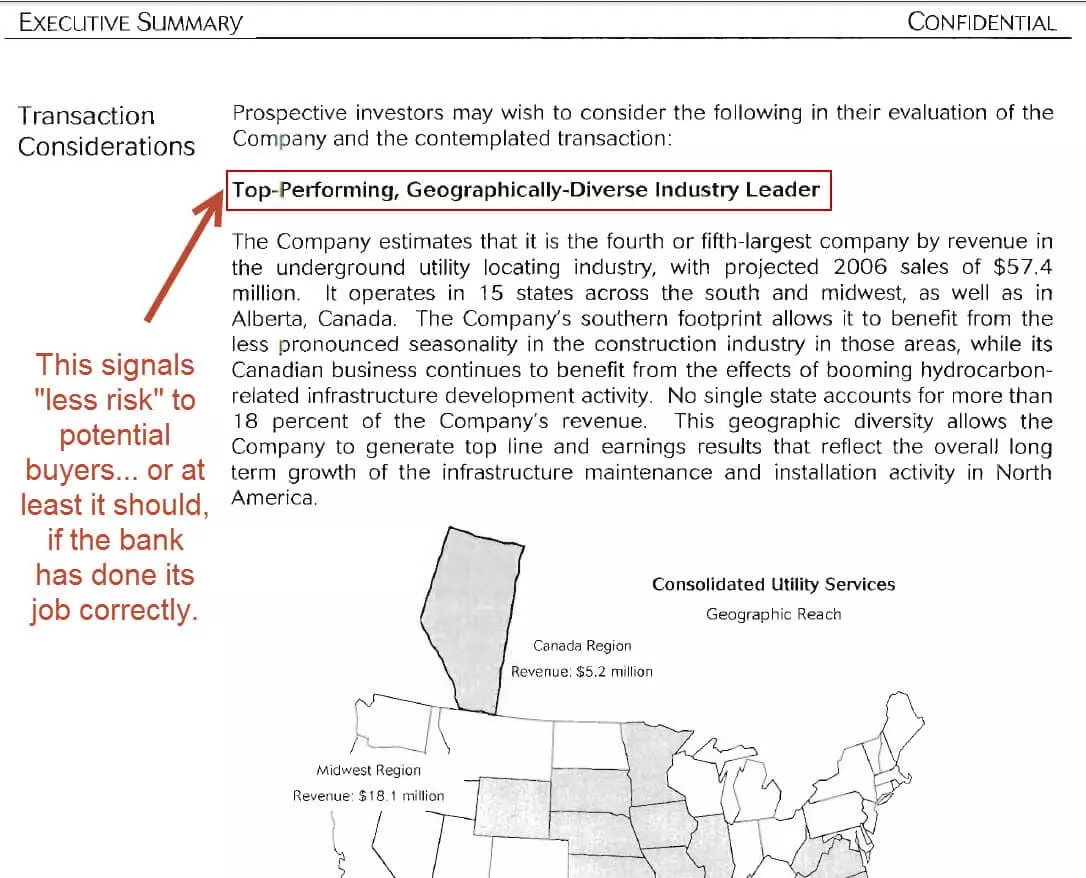

If you turn to “Transaction Considerations” on page 10, you can see these points in action:

“Top-Performing, Geographically Diverse Industry Leader” means “less risk” - hopefully. Then the bank lists the industry’s attractive growth rates, the company’s blue-chip customers (even lower risk), and its growth opportunities, all in pursuit of the five points above.

The “Financial Performance” Section of the CIM

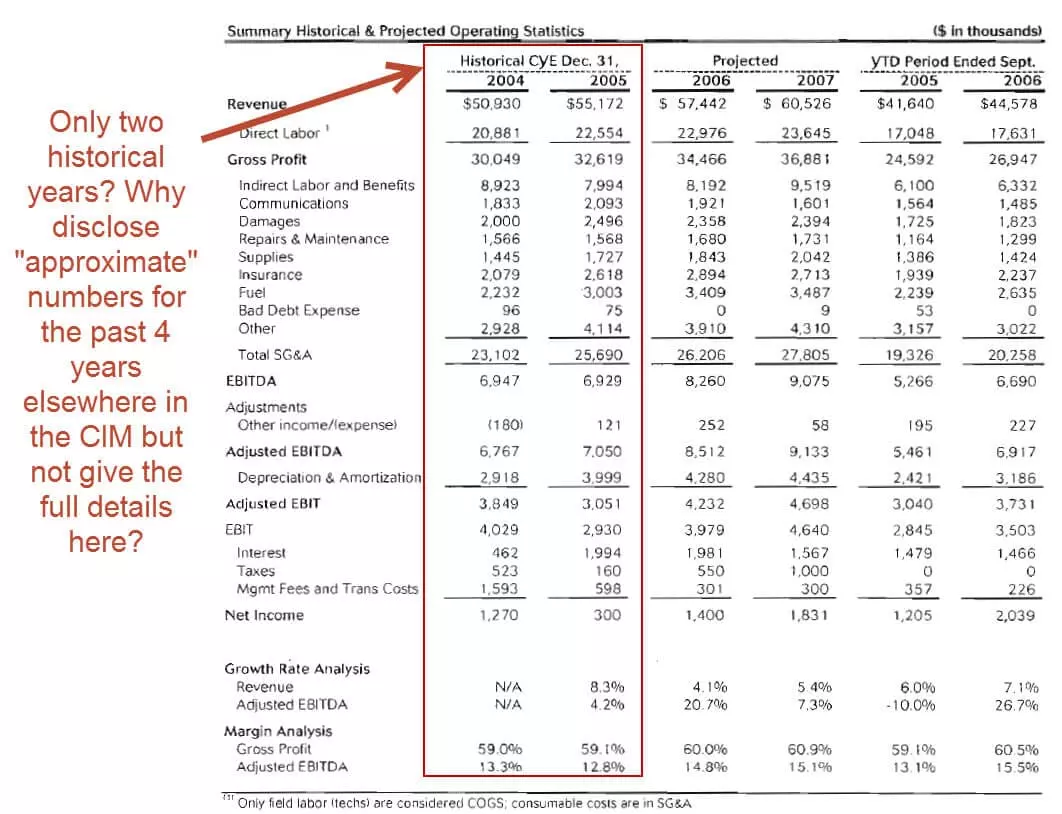

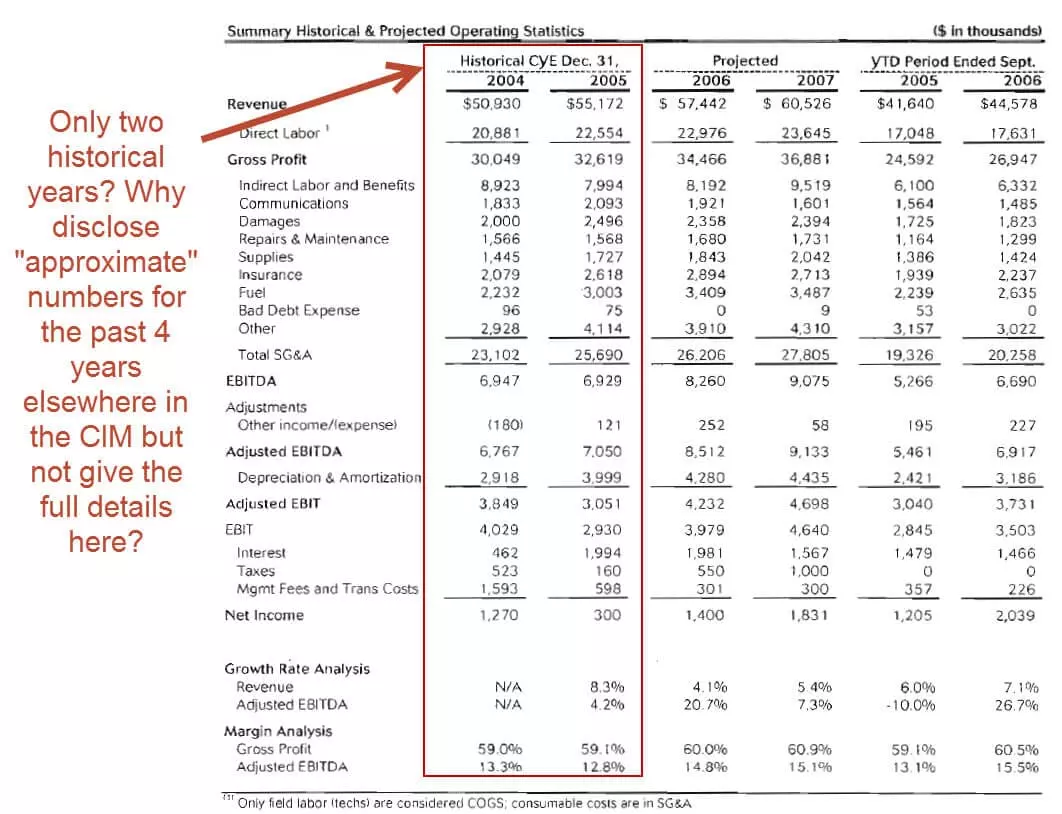

The “Financial Performance” section also takes up a lot of time because you have to “dress up” a company’s financial statements… without outright lying. So it’s not as easy as pasting in the company’s historical financial statements and then making simple projections - think “reasonable spin.” Here are a few examples of “spin” in this CIM:

- Only Two Years of Historical Statements - You normally like to see at least 3-5 years’ worth of performance, so perhaps the bankers showed only two years because the growth rates or margins were lower in the past, or because of acquisitions or divestitures.

- Recurring Revenue / Contract Spin - The bankers repeatedly point to the high renewal rates, but if you look at the details, you’ll see that a good percentage of these contracts were won via “competitive bidding processes,” i.e. the revenue was by no means locked in. They also spin the lost customers in a positive way by claiming that many of those lost accounts were unprofitable.

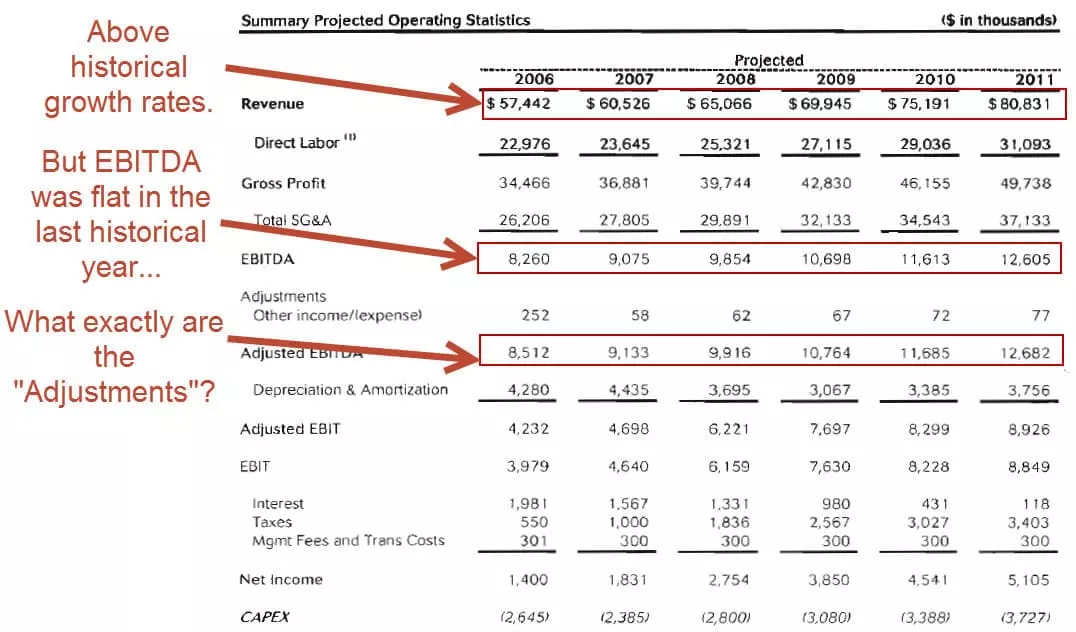

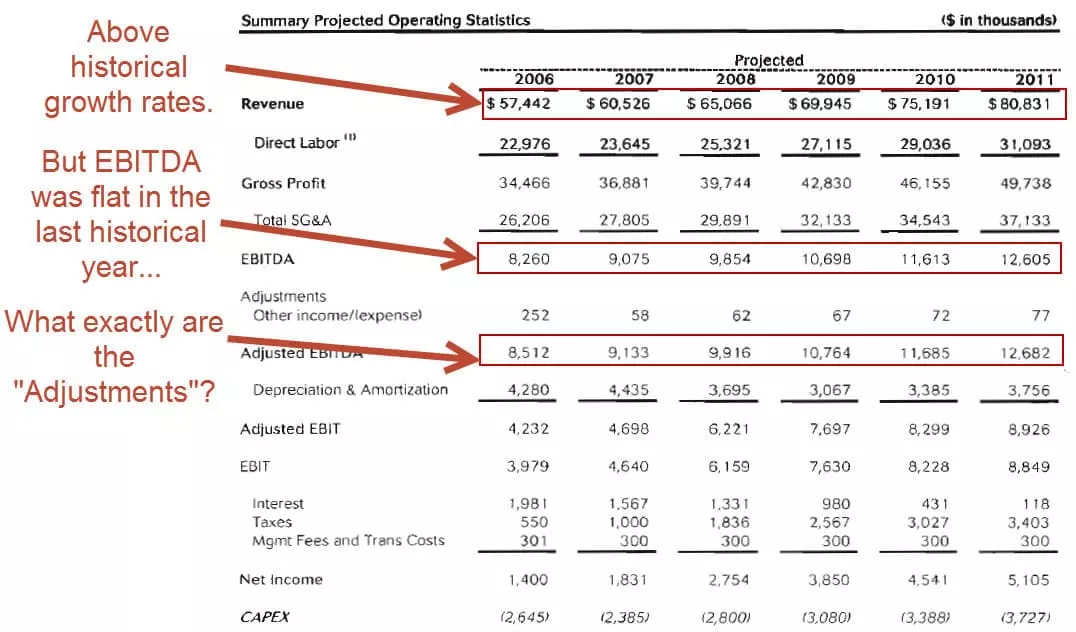

- Flat EBITDA and Adjusted EBITDA Spin - EBITDA stayed the same at $6.9 million in the past two historical years, but the bankers spin this by saying that it remained “stable” despite significantly higher fuel costs… glossing over the fact that revenue increased by 8%. Figures like “Adjusted EBITDA” also lend themselves to spin since the adjustments are discretionary and are chosen to make a company look better.

- Highly Optimistic Projected Financials - They’re expecting revenue to grow by 7.5% each year, and EBITDA to increase from $8.3 million to $12.6 million over the next five years - despite no EBITDA growth in the last historical year.

As a banker, your job is to create this spin and portray the company favorably without going overboard.

Does Any of This Make a Difference?

Yes and no. Buyers will always do their due diligence and confirm or refute everything in the CIM before acquiring the company. But the way bankers position the company makes a difference in terms of which buyers are interested and how far they advance in the process. Just as with M&A deals, bankers tend to add more value in unusual situations - divestitures, distressed/turnaround deals, sales of family-owned private businesses, and so on. Example: In a sell-side divestiture deal, the subsidiary being sold is always dependent on the parent company to some extent. But in the CIM, bankers have to take care with how they describe the subsidiary. If they say, “It could easily stand on its own, no problem!” then more private equity buyers might show an interest in the deal and submit bids. But if the PE firms find out that the bankers were exaggerating, they might drop out of the process very quickly. On the other hand, if the bankers say that it will take significant resources to turn the subsidiary into an independent company, the deal might never happen due to a lack of interest from potential buyers. So it’s a careful balancing act between hyping up the company and admitting its flaws.

How Do You Read and Interpret the Confidential Information Memorandum in Private Equity and Other Buy-Side Roles?

You will receive A LOT of CIMs in most private equity roles, especially at middle-market and smaller funds. So you need a way to skim them and make a decision in 10-15 minutes about whether to reject the company upfront or keep reading. I would recommend these steps:

- Read the first few pages of the Executive Summary to learn what the company does, how big it is in terms of sales, EBITDA, cash flow, etc., and understand its industry. You might be able to reject the company right away if it doesn’t meet your investment criteria.

- Then, skip to the financials at the end. Look at the company’s revenue growth, EBITDA margins, CapEx and Working Capital requirements, and how closely FCF tracks with EBITDA. The financial projections tend to be highly optimistic, so if the math doesn’t work with these numbers, chances are it will never work in real life.

- If the deal math seems plausible, skip to the market/industry overview section and look at the industry growth rates, the company’s competitors, and what this company’s USP (unique selling proposition). Why do customers pick this company over competitors? Does it compete on service, features, specializations, price, or something else?

- If everything so far has checked out, then you can start reading about the management team, the customer base, the suppliers, and the actual products and services. If you make it to this step, you might spend anywhere from one hour to several hours reading those sections of the CIM.

Applying the Analysis in Real Life

Here’s you might apply these steps to this memo for a quick analysis of CUS:

First Few Pages: It’s a utility services company with around $57 million in revenue and $9 million in EBITDA; the asking price is likely between $75 million and $100 million with those stats, though you’d need to look at comparable company analysis to be sure.

There has been solid revenue and EBITDA growth historically, but the company was formed via a combination of smaller companies so it’s hard to separate organic vs. inorganic growth. At this point, you might be able to reject the company based on your firm’s investment criteria: for example, if you only look at companies with at least $100 million in revenue, or you do not invest in the services sector, or you do not invest in “roll-ups,” you would stop reading the CIM. There are no real red flags yet, but it does seem like customers are price-sensitive (“…price is generally one of the most important factors to the customer”), which tends to be a negative sign.

Financials at the End: You can skip to page 58 now because if the deal math doesn’t work with management’s highly optimistic numbers, it definitely won’t work with realistic numbers. Let’s say your fund targets a 5-year IRR of 20% and expects to use a 5x leverage ratio for deals in this size range. The company is already levered at ~2x Debt / EBITDA, so you can only add 3x Debt / EBITDA. If you do the rough math for this scenario and assume a $75 million purchase price, a $75 million purchase enterprise value represents a ~9x EV / EBITDA multiple, with 3x of additional debt and 2x for existing debt, which implies an equity contribution of 4x EBITDA (~$33 million). If you re-sell the company in five years for the same 9x EBITDA multiple, that’s an Enterprise Value of ~$113 million (9x * $12.6 million)… but how much debt will need to be repaid at that point? To answer that, we need the company’s Free Cash Flow projections… which are not shown anywhere. However, we can estimate its Free Cash Flow with Net Income + D&A - CapEx and then assume the working capital requirements are low (i.e., that the Change in Working Capital as a percentage of the Change in Revenue is relatively low). If you do that, you’ll get figures of $3.9, $3.6, $3.8, $4.5, and $5.1 million from 2007 through 2011, which adds up to $21 million of cumulative FCF.

But remember that the interest expense will be significantly higher with 5x leverage rather than 2x leverage, so we should probably reduce the sum of the cumulative FCFs to $10-$15 million to account for that. Initially, the company will have around $42 million in debt. By Year 5, it will have repaid $10-15 million of that debt with its cumulative FCF generation. We’ll split the difference and call it $12.5 million. At a 9x EV / EBITDA exit multiple, the PE firm gets proceeds of $113 million - ($42 million - $12.5 million), or ~$84 million, upon exit, which equates to a 5-year IRR of 20% and a 2.5x cash-on-cash multiple. I would reject the company at this point. Why? Even with optimistic assumptions - the same EBITDA exit multiple and revenue and EBITDA growth above historical numbers - the IRR looks to be around 20%, which is just barely within your firm’s desired range. And with a lower exit multiple or more moderate growth, the IRR drops below 20%. The EBITDA growth looks fine, but FCF generation is weak due to the company’s relatively high CapEx, which limits debt repayment capacity. It seems like the company doesn’t have much pricing power, since quite a few contracts were renewed via a “competitive bid cycle process.” Low pricing power means it will be harder to maintain or improve margins. On the other hand, you might look at this document and interpret it completely differently. The numbers don’t seem spectacular for a standalone investment, but this company could represent an excellent “roll-up” opportunity because there are tons of smaller companies offering similar utility services in different regions (see “Pursue Additional Add-on Acquisitions” on page 14) (for more, see our tutorial to bolt-on acquisitions). So if your firm focuses on roll-ups, then perhaps this deal would look more compelling. And then you would read the rest of the confidential information memorandum, including the sections on the industry, competitors, management team, and more. You would also do a lot of research on how many smaller competitors could be acquired, and how much it would cost to do so.

What Next?

These examples should give you a flavor of what to expect when you write a confidential information memorandum in investment banking, or when you read and interpret CIMs in private equity. I’m not going to say, “Now write a 100-page CIM for practice!” because I don’t think such an exercise is helpful - at least, not unless you want to practice the Ctrl + C and Ctrl + V commands. So here’s what I’ll recommend instead:

- Pick an example CIM from the list above, or Google your way into a CIM for a different company.

- Then, look at the Executive Summary and Financial Performance sections and find the 5-10 key areas where the bankers have “dressed up the company” and spun it in a positive light.

- Finally, pretend you’re at a private equity firm and follow the decision-making process I outlined above. Take 20 minutes to scan the document and either reject the company or keep reading the CIM.

Bonus points if you can locate typos, grammatical errors, or other attention-to-detail failures in the memo you pick.

Any questions?

— Want more? You might be interested in a detailed tutorial on investment banking PowerPoint shortcuts.