In 2000, the bursting of the dot-com bubble shook the financial world, wiping out $6.2 trillion worth of household wealth over the next two years. Five years later, the housing market crashed, resulting in a staggering $6 trillion loss in real estate value owned by U.S. households from 2007 to 2009. Surprisingly, even though the losses were similar in magnitude, the housing crash led to the Great Recession, while the dot-com crash only caused a mild recession.

So, what explains this stark difference in outcomes? In their forthcoming book, "House of Debt," the authors argue that the distribution of losses played a crucial role. The housing crash hit hardest those with the least capacity to bear the losses, disproportionately affecting poor homeowners who were forced to cut back on spending. On the other hand, the tech crash primarily impacted the rich, who had minimal debt and continued their spending unabated.

Let's delve deeper into the reasons behind this divergence and the impact it had on different segments of society.

The Vulnerability of Poor Homeowners

The chart below illustrates the distribution of housing as a fraction of all assets for U.S. homeowners in 2007. For the poorest homeowners, housing comprised nearly 80 percent of their total assets, making them highly vulnerable to a crash in housing prices. In contrast, the richest households had housing as a smaller component of their overall asset portfolios, constituting less than 20 percent.

Caption: The distribution of housing as a fraction of all assets for U.S. homeowners in 2007.

Caption: The distribution of housing as a fraction of all assets for U.S. homeowners in 2007.

The Role of Leverage

The poorest homeowners had significant mortgages, while the wealthiest had relatively small ones compared to the value of their homes. This chart demonstrates the mortgage balance as a fraction of home value for each net-worth quintile in 2007. It's worth noting that poor homeowners relied heavily on leverage to purchase their homes.

Caption: The mortgage balance as a fraction of home value for different net-worth quintiles in 2007.

Caption: The mortgage balance as a fraction of home value for different net-worth quintiles in 2007.

Leverage can be perilous for borrowers when home values plummet. For instance, if someone has an $80,000 mortgage on a $100,000 home, and the home's value drops by 20 percent to $80,000, the homeowner loses $20,000, which represents a 100 percent loss of their equity in the home. In essence, a 20 percent decline in home prices translates into a 100 percent loss for leveraged homeowners.

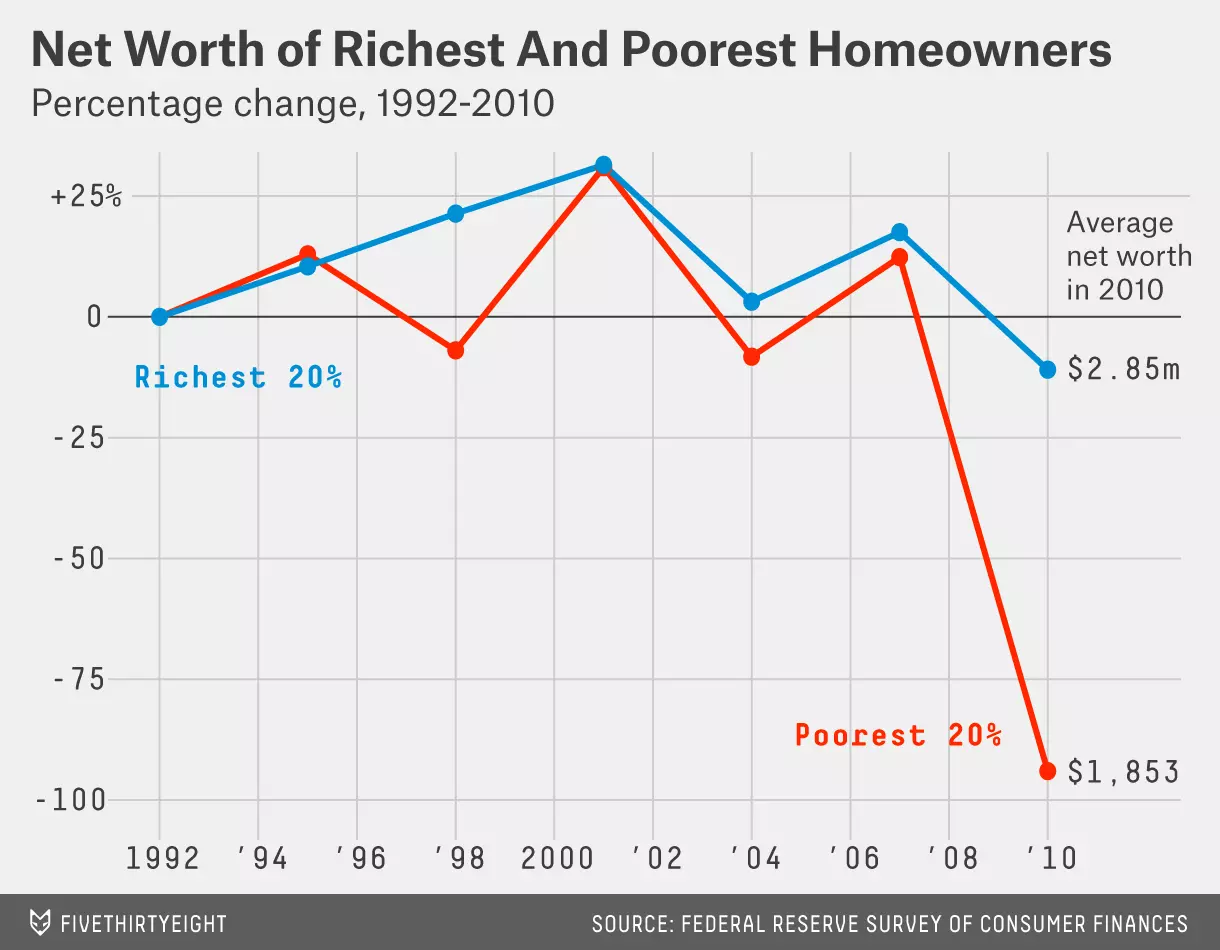

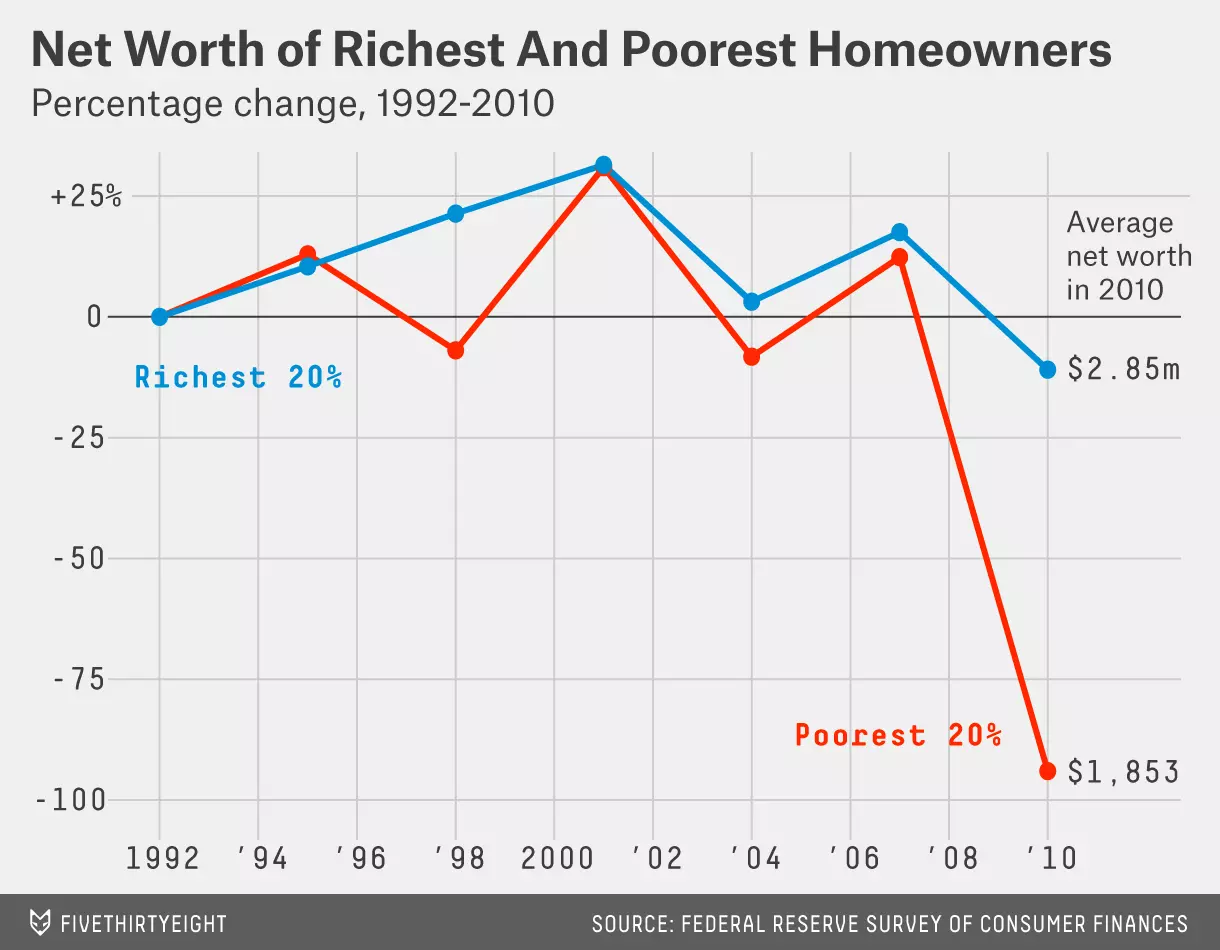

The Impact on Wealth Distribution

During the Great Recession, the poorest homeowners experienced a significant decline in net worth. Their net worth, which stood at $30,000 in 2007, practically vanished by 2010. These individuals bore the brunt of the housing shock, suffering a substantial blow to their financial well-being. In contrast, the wealthiest homeowners saw only a minor decline in their net worth. Although the dollar amount of their losses was substantial, they were essentially back to their 2005 level of wealth.

The poor tend to cut back on spending much more for the same dollar decline in wealth compared to the rich. This finding, consistently observed in macroeconomics, holds true in the context of housing, fiscal rebate checks, and credit card limits. It is intuitive as well; if Bill Gates loses $30,000 in a bad investment, he won't curtail his spending, whereas a household with only $30,000 in savings would inevitably slash their expenses.

The Importance of Distributional Issues

Traditionally, macroeconomic models have overlooked distributional matters, treating all households as a single "representative agent." This approach assumes that differences in spending responses to wealth shocks are inconsequential, contrary to empirical findings.

For instance, former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, in his book on the Great Depression, downplayed the significance of distributional issues, suggesting that differences in spending propensities due to wealth would have to be "implausibly large" to explain the decline in spending during the 1930s. Some economists hold a similar view regarding the recent recession.

However, the contrasting effects of the 2008 housing crash and the early 2000s tech crash underscore the centrality of distributional issues in macroeconomics. As demonstrated by the current interest in economist Thomas Piketty's book, "Capital in the Twenty-First Century," both experts and the general public are increasingly recognizing the crucial role of wealth inequality in understanding the broader economy.

In conclusion, the housing bubble had a more profound impact on the economy than the tech bubble due to the distribution of losses. Poor homeowners, burdened by heavy debt and high leverage, suffered significant financial setbacks, leading them to drastically reduce their spending. Recognizing the importance of distributional issues is key to comprehending the dynamics of economic downturns and fostering a more inclusive and resilient economy.