The dynamics of inflation have undergone significant changes in the past year. From June 2022 to March 2023, annual Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation dropped from 9.1 percent to 5.0 percent. This decline can be attributed to the easing of two major drivers of inflation: energy and core goods. Energy prices, known for their volatility, have seen a decrease in recent months and even turned negative in March compared to the previous year. Additionally, improvements in supply chains have contributed to a decrease in core goods inflation over the past few quarters.

Figure 1: Contributions of Energy Prices to Headline CPI Inflation

Figure 1: Contributions of Energy Prices to Headline CPI Inflation

However, housing's contribution to inflation has significantly increased, now accounting for a third of the consumer basket of items measured in CPI. Even small increases in housing prices can have a disproportionate impact on inflation. Last June, housing accounted for a fifth of inflation, contributing 1.7 percentage points. By March 2023, housing's contribution rose to 2.6 percentage points, making up half of the annual CPI inflation. To put this into perspective, housing would typically contribute about 1 percentage point to inflation before the pandemic.

One can find evidence, along with some outside analysts, suggesting that housing inflation could ease in the coming months. In this article, we will explore why housing inflation increased and how the Consumer Price Index's measurement of housing prices may influence their potential path going forward.

Demand and Supply Factors

Recent housing inflation seems to have roots in both demand and supply factors. Experts such as Mondragon & Wieland (2022) and Kmetz et al (2022) emphasize pandemic-related demand channels, such as rises in internal migration and work-from-home (WFH) arrangements. The flexibility of WFH may influence where working-age families choose to live and the type of housing they demand. However, it is uncertain how persistent this pandemic shift in demand will be.

Furthermore, higher demand coupled with long-standing housing supply constraints in certain metropolitan areas has exacerbated price increases. In response, the Biden Administration has made increasing the supply of affordable housing a top priority. Initiatives such as the Housing Supply Action Plan, which incentivizes land use and zoning reform, as well as financial support for new construction in the President's latest Budget proposal, aiming to invest over $175 billion in housing over the next decade.

Measurement Issues

Several measurement issues affect the official housing inflation statistics. Market data, such as Zillow's, show that while the growth in the price of newly-signed leases remains elevated, it has slowed considerably since last year, indicating a cooling rental market.

Figure 2: Growth in the Zillow Observed Rent Index

Figure 2: Growth in the Zillow Observed Rent Index

However, the Consumer Price Index may not reflect such a slowdown immediately. This is because the CPI measures both new and existing leases, with existing leases updating infrequently, usually once or twice a year. Consequently, it takes time for these measurement issues to reflect current market dynamics. As a result, many policymakers and private observers, including CEA, track housing and non-housing services separately when analyzing the components of overall inflation.

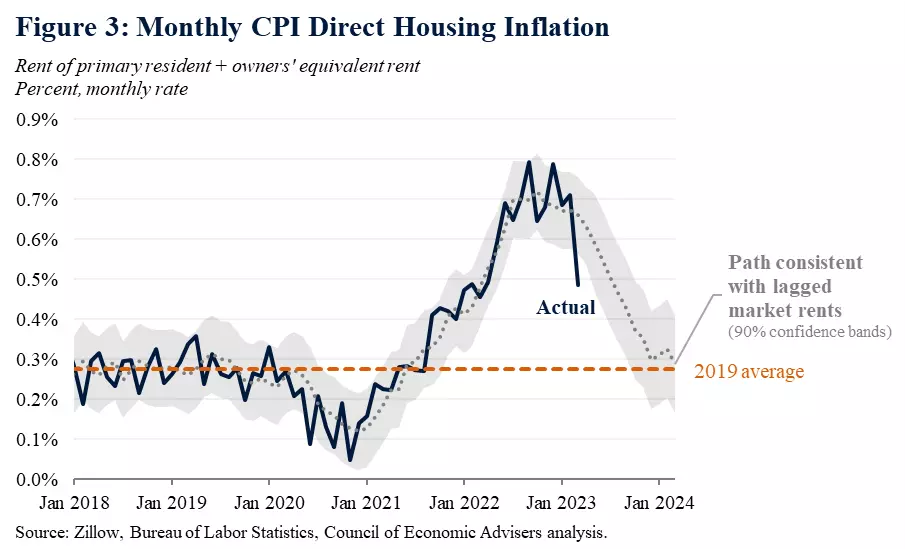

CEA models monthly CPI housing inflation using a population-weighted version of the Zillow median rent index to capture the lagged market pressures. Similar to a recent Bureau of Labor Statistics paper (Adams et al., 2022), CEA finds that it takes approximately 12 months for changes in market rents to fully incorporate into housing CPI. The model suggests that the slowdown in market rental growth in the previous year will likely begin to show up in CPI in the second half of 2023.

Figure 3: Monthly CPI Direct Housing Inflation

Figure 3: Monthly CPI Direct Housing Inflation

Interestingly, in March, monthly CPI housing inflation was significantly weaker than predicted by the model. While this decline would be welcome news if sustained, it's essential to note that one month of data is insufficient to determine whether this decline reflects actual developments or is just data noise. If the latter, housing inflation may partially or fully reverse in April.

In conclusion, although overall inflation has cooled considerably since last June, housing inflation remains high. Strong pandemic-related demand and long-standing supply challenges in various regions contribute to this trend. Market data suggests that rental growth has recently declined, and it will take some time for these declines to be fully reflected in official inflation data. The Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) will continue to closely monitor these data developments and other factors that impact inflation.

[1] "Housing" in the context of this article refers to the sum of two CPI categories: rent of primary residence and owners' equivalent rent (OER).

[2] It is important to note that "housing inflation" in CPI is not a measure of the change in housing purchase prices directly. Instead, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks the rental value of different housing units. For rental units, this refers to the price of new and existing leases. For owner-occupied units, the BLS calculates the "owners' equivalent rent," an estimate of the rental value based on lease prices of similar units.